This is a lecture 3 of the Systems Engineering curriculum from MIT and edX, Engineering the Space Shuttle.

Links to the lectures:

- Origins of the Space Shuttle or The Making of a new Program

- Development of the Space Shuttle

- Bureaucratic Space War

- Political History of the Space Shuttle

- Space Shuttle Orbiter Subsystems

- Orbiter Structures & Thermal Protection System (TPS)

- Space Shuttle Main Engines

Robert Seamans raises a very important point in his lecture: What you do depends on many other people including external to you who make vital decisions and often incorrect ones, decisions that affect capabilities decades ahead. You can do your best to explain your position to the decision makers but be prepared to accept that they have their reasons and motivations, often not related to your project.

This is from the lecture:

It was far along, lots of expenses had gone into it including major facility construction out of Vandenberg. So, I had my day in court, it was a sunny afternoon, I got General Stewart who was very involved in the MOL to join me, and Mel Laird, and we went over there, it was just Kissinger and president Nixon, and I had a few simple-minded charts that showed what we’re going to do from a resolution standpoint if we kept going with the MOL, and what that would mean in terms of understanding more clearly what was going on in a given situation. I had my half hour in court, I could see a band outside getting ready to play, so I knew that the president was about to be rushed out for some kind of a ceremony. Monday morning I got a call from Kissinger and he said, “Bob – and I can’t really imitate his German accent – that was a very, very fine presentation,” and the day later I found out that MOL was canceled. President Nixon sat there the whole time, he had a yellow Fools Cap, and he took prodigious notes of everything I was saying, which was nerve-racking, the President United States bothering with what I’m saying.

Here’s a fascinating example of the decisions made by the politicians at the very highest level of power in 1960s that affected United States capabilities of this day, 60 years later!

NASA Associate Administrator 1960-1965. NASA Deputy Administrator 1965-1968

Introduction by Jeff Hoffman

This lecture is significant because it gives you a chance to hear from Dr. Robert Seamans. You’ve already heard numerous references to Bob Seamans who was Secretary of the Air Force during the beginning of the Space Shuttle Program. Dr. Seamans had a long career combining teaching at MIT, working in the aerospace industry and at NASA both as Associate and Deputy Administrator during the Apollo program. We invited him to come and talk about his recollections of how the military view of the use of the Shuttle was since, as you’ve already heard, military requirements were critical in determining the final configuration of the space Shuttle.

Dr. Seamans mentions the MOL program, the Manned Orbiting Laboratory, a concept for an early space station which the Air Force wanted to build. The Air Force selected a group of military astronauts to train for the MOL program. They would have been launched in Gemini capsules on Titan rockets. Well, the program was cancelled in 1969 and some of the MOL astronauts were transferred to NASA where they eventually flew on the Space Shuttle. Bob Crippen, the pilot on the first Shuttle flight, was one of these original MOL astronauts.

It turned out that on the day that Bob Seamans gave his lecture to the class I had to be out of town, so I asked one of my colleagues, Pete Young, a colonel in the US Air Force, who was on loan to our department for several years, to introduce Dr. Siemens.

You should pay special attention when Dr. Seamans discusses his initial reservations about the policy that all payloads should be launched on the Shuttle, which of course was necessary to ensure a sufficient flight rate to keep the costs down. Bob points out that human lives should not be put at risk just to launch satellites which can be launched with unmanned vehicles. And this actually is the conclusion that NASA finally came to after the Challenger accident.

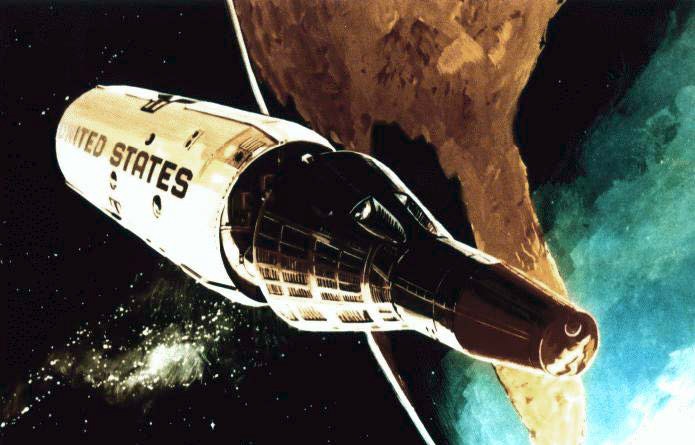

You’ll hear a question about why reusable unmanned vehicles couldn’t be developed to launch satellites. Dr. Seamans was noncommittal on this, but remember that this lecture took place back in 2005, long before SpaceX and Blue Origin developed their recoverable and reusable first stages an example of which is shown while Dr. Seamans is talking.

Early History of the Space Shuttle and NASA’s Relationship with the Military

Let me take you back to the early 60s. That’s when I joined NASA as a general manager. Before we knew it, we’ve gone from a billion dollar a year operation with the Mercury program to the situation where we were given the assignment of putting men on the moon and that was a gigantic shift in our responsibility. In all of the planning and the discussions and so on we wanted and we did work very closely with the Department of Defense. The Department of Defense had all kinds of assets that were going to be required in the space program, the Navy, for example, to pick up the astronauts.

We had to construct very large facilities, the most famous and obvious was the vertical assembly building and the launch facility at the Cape from which the Shuttle took off.

There already was Cape Canaveral and there was no room for what we were going to do to fit there. We looked at a seven different sites and finally decided to camp on Merritt Island, which is just across the river from Cape Canaveral, because the Department of Defense had all kinds of facilities down there with a tracking range and so on, but the biggest support that we got was in building of those facilities. There was absolutely no confidence in NASA ability to build the largest structure in the world, the VAB, or many other facilities for assembly and for tests and so on. The core of engineers was a major part of the operation.

I’m bringing this out, because we had to figure out how far we’re going to go with our large vehicles on a shared basis. This is before anybody thought of a manned Shuttle that would carry stuff up and stick it into orbit. So we put together a planning organization consisting of NASA and the Department of Defense that operated for over a year’s time.

One of the big emphasis was the use of the Titan which was coming along to the point where we thought the earliest version would be suitable for the Mercury program. At that time in 1961 we were thinking that Mercury will only weigh 3,000 pounds and you were going to put one man on it. You couldn’t do much with it but if we could in effect enlarge it and have a more powerful vehicle in Atlas, namely the Titan, we could really have a vehicle that would have some capability to run through a lot of the orbital operation and so on, that will be ultimately required for going to the Moon. And out of that came the planning for the Titan III, the Titan IV, and vehicles that are very important to our defense capability as well.

In 1968 I got a call one day from Melvin Laird who had been designated by Nixon to be the next Secretary of Defense, that’s when he asked if I would be willing to be the Secretary of the Air Force.

One thing that I inherited right off the bat was a maned orbital laboratory. Even then it was clearly in some jeopardy. When program start getting a ceiling built in where they say: We’re going to keep it going, but it’s going to be kept going at a level of… And I figured what the level was for MO, something like a 500 million or like that.

Any large program over time always has opposition to it and there’s more time for it to be shot down and ultimately eliminated.

I realized that it was in deep trouble when I was over in the bureau of the budget, talking to a junior member, and he said, “I hope you realize that the Shuttle’s in deep trouble from a standpoint of support here in the White House.” I went back to Mel Laird and I said, “Look, one thing I want to do is to have one shot with the president to see if he fully understands what the capability of MOL will be.”

It was far along, lots of expenses had gone into it including major facility construction out of Vandenberg. So, I had my day in court, it was a sunny afternoon, I got General Stewart who was very involved in the MOL to join me, and Mel Laird, and we went over there, it was just Kissinger and president Nixon, and I had a few simple-minded charts that showed what we’re going to do from a resolution standpoint if we kept going with the MOL, and what that would mean in terms of understanding more clearly what was going on in a given situation. I had my half hour in court, I could see a band outside getting ready to play, so I knew that the president was about to be rushed out for some kind of a ceremony. Monday morning I got a call from Kissinger and he said, “Bob – and I can’t really imitate his German accent – that was a very, very fine presentation,” and the day later I found out that MOL was canceled.

President Nixon sat there the whole time, he had a yellow Fools Cap, and he took prodigious notes of everything I was saying which was nerve-racking, the President United States bothering with what I’m saying.

The next step along the way was going to be 8 launches of the Apollo lunar program. Nixon cut that back to 2 sort of arbitrarily and there were no plans for using those assets.

Jim Webb was my boss at NASA and I used to see him. He was very, very ill a lot of part of his life, and I dropped by and he’d asked me strange questions like “What do you plan to do with your life before you kick the bucket?” Kind of questions like that. And “I haven’t got long to live.” And I’d say “You’re doing fine, Jim. And I’m just going to work along to see what I can do to help out here and there.”

But anyway, his big thrust was, we felt we were building a major capability for the country and now it’s all being washed away and what’s going to replace it?

The Shuttle came up as an option and it makes an awful lot of sense to recover something. One could easily visualize transportation system for the country where every time a 747 when across the country with a payload everybody jumped out and then you threw in the ocean. It didn’t seem to make much sense, you just knew it had to be more efficient to reuse something. Although, with Jim and I, we had looked into that possibility, we weren’t recovering the Geminis, why didn’t we use them again? We found out we were going to put probably 75% of the original cost into reactivating the Geminis. I had a hunch that it wasn’t going to be quite as simple as landing an airplane and then taking off again. The Air Force was going to be one of the prime uses of the Shuttle and the question was, “How large the bomb bay, sorry, not the bomb bay, how large the experimental bay have to be for the missions that were going to be carried out?” There was no thought of putting armament aboard the Shuttle. I misspoke.

And then the question was, “How rapidly did you have to recover it if something happened and you wanted to bring something back in a hurry?” To bring it back, you had to make a coplanar change and that was going to take a certain amount of energy, to put it mildly.

Those are many of the issues and as I remember it, my friends in NASA thought the Air Force was being pretty tough on them.

More and more it appeared that we were going to not be allowed to put anything in space except through the Shuttle. And I saw that to be eminently wrong to think that you’re going to have to risk the life of astronauts every time you wanted to put any kind of a satellite in orbit. From the standpoint of individuals looking at cost, you just have one vehicle and use it and use it and use it and thereby supposedly cutting the cost had a lot of charm. We reached the point where we had to try to do something about it and we made an appointment with the then Secretary of the Air Force and said, “You’ve just got to be stashing away Titan somewhere so that if we run into trouble with the Shuttle we’re going to be able to move over and put these very important payloads into orbit.” And then they had the Challenger accident, and at that point this major fallacy in policy was changed back where it should have been. You just shouldn’t rely on a single vehicle.

‒ You wanted reusability, but you also didn’t want to risk life of the astronautics. Why not make a reusable unmanned vehicle?

My comment. Robert Seamans did not answer this question leaving instead a challenge for the students to create such a system. Reusable rockets were designed and tested in 1980s and 1990s and the following video tells the history. The concept is simple: you have to take extra fuel in order to land the rocket back. In the early days, the cost of maintenance and recertification was too high.

We worked very hard on the proposals to bring back satellites that were out of fuel or needed refurbishment, but when I was referring to landing a Shuttle with payloads in the bay, that is for a failed mission. If for some reason the payload could not get ejected, you still had to be able to land back with a very heavy spacecraft and glide on in and land safely. That turns out to be a really hard thing to do, especially if you’re carrying solids and liquids on board that are close to being ready to ignite, so to speak.

There was a talk of retrieving satellites and as you know NASA did bring back some small satellites, the Palapa one from Hughes, and also did a lot of very innovative repairs in space. But when we looked at it from a customer point of view, it turns out, there’s a lot that wears out in satellites, not just using a propellant, but processors degrade due to the radiation, solar panels degrade due to microdust and things like that, And so, bringing back satellites for reuse was never felt at the time we looked at it to be worthwhile thing to do.

And that ties indirectly with what I was saying about recovering a Gemini and of course on top of that the fact that you are landing them in the water so they got a good dowsing of salt, the degradation of the Gemini was such that we just didn’t think it made any sense to try to refurbish them.

Military never seriously went after the capture and refurbish or release. They really went after re-launch and deployment.

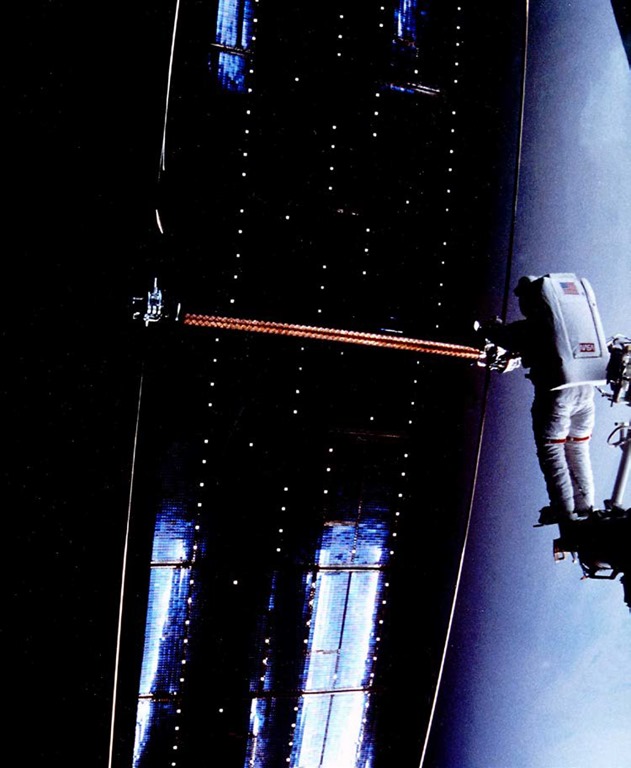

I’d say that the most successful story of refurbishment is a Hubble Space Telescope, and not for the reasons that you think of. When you hear about stories with the Hubble Space Telescope you hear about Jeff Hoffman going up there and changing processors and fixing the objects. Also in those missions they replaced solar panels that were causing huge problems due to thermal, warpage and shrinkage and canning due to thermal stresses, and so there are placements of those solar panels which turned out to be not very good as initially designed and that is one of the really true success stories of man in space.

There is a very nice video of the lady astronaut who did the replacement of the solar panels on Hubble pushing out and releasing the solar panels, and the things fly away in the sunshine looking like giant butterfly wings reflecting all the colors and then funny fall into the atmosphere. It’s almost poetic, it’s amazing.

Hubble Space Telescope: repair report

One of the considerations right from the beginning was that Hubble should be a serviceable satellite. It was designed so that you could get inside of it relatively easily. And I frankly, I don’t know of any other satellite that was really designed quite that way.

But it wasn’t designed to have to replace the solar panels. One of the real tricks when the astronauts first got to it was to unravel some of the wires that got caught so that the panels could spread out and start to operate again.

If you go back to Skylab which was the next to last launching of the Apollo, on that one we decided to take what was the third stage of the Saturn and just got it not have any propulsion and fit it out to be a spacecraft, namely a space station.

Apollo Image Gallery

Skylab, NASA’s First Space Station, Was Nearly a Disaster

Payloads are coming from Vandenberg, they are not dummy, they are real. They have standing requirements for these types of things. The national needs go on, international stages we know are filled with new actors and new threats, we have what’s called unsymmetrical warfare, things that are hard to counter by conventional means. Back in the 70s and 80s we had symmetrical warfare, submarines versus submarines, missiles first missiles. Now, as we know, it’s much harder, much tougher, but the needs are still there.

The collaboration between NASA and the military is not in terms of payloads, it is in the exchange of technologies, things like development of more efficient sensors, processors, that sort of thing. It’s everybody’s benefit. For example, they have more powerful, faster rad-hard space processors. Everybody wins in that type of situation.

One thing I forgot to mention in regard to manned orbital laboratory, it was thought at that time that by having men there and their ability to inspect a fairly wide swath, that they would have time while flying over that swath to do some searching and could do a better job of detecting possible items of tremendous interest from a military standpoint, than trying to do it all automatically. And a course, what finally washed out that argument was the ability to have satellites that had almost instantaneous transmission of information back home.

They were going to take off on a Titan, and they were going to be on board of Gemini, and they were going to have a laboratory of sorts which would have the necessary reconnaissance and other equipment aboard. It had a Gemini type of return vehicle but it was definitely going to be quite small and cramped.

Landings were all on water. The reason is very simple. If you take a look where all the launch sites were for the Soviets, if they aborted, they had capability of getting down on land. When operating out of Cape Canaveral, if you aborted you had to come down on water. The question was then, was it a worthwhile to have the capability of doing both? That just added weight and so we stuck with the water, and they stuck with the land.